What does a church do when the boom-town it grew in closes down and everyone leaves? The answer may pleasantly surprise you.

It’s an exhilarating thing to plant a new church in a boom town and ride the wave of success, but altogether a different experience when your town closes down and over 95% of the population vanishes. Do you shut down or re-imagine your purpose, or both?

Before The Boom

A once thriving uranium boom mining town, Jeffrey City now sits forgotten, forlorn, and rotting away in the Wyoming sun, rain, and snow. Tumbleweeds roll through the now deserted streets and ageing buildings that stand as a monument to the past.

The town had its start thanks to Beulah Peterson Walker, who in 1931 found herself down on her luck. Her husband, a World War One veteran who suffered from a gas attack during the war, was given six months to live. Working on theory that clean air would help his damaged lungs, she decided to head west with her husband and they eventually settled in an old abandoned farmstead south of the Oregon Trail. They fixed the place up and reinvented it as a waystation for the passing travellers. by.

They called their new homestead “Home on the Range” and their punt paid handsome dividends as her husband lived for another twenty years. Little did they know that their little slice of paradise would become the center of a corporate mining town, because unbeknown to them their homestead sat in the shadows of hills filled with uranium.

The Boom Begins

After the atomic age broke on America, uranium became much sought after, and a speculator named Bob Adams discovered the buried wealth that was waiting to be dug up nearby. This discovery would forever alter the landscape and fortunes of this area.

Thanks to the financial heft of an investor called Dr C.W. Jeffrey, capital was provided to begin a mining enterprise. And so began Western Nuclear which began mining operations in 1957.

In homage to Jeffrey’s investment, Adams named the soon to explode boom town after him. Thus was Jeffrey City born and Beulah’s original “Home on the Range” was subsumed by development.

Jeffrey City grew fast. Streets appeared, utilities were established, schools, shops, and hotels were built and soon housing developments took care of the housing needs of miners and their families.

Churches were founded as well as a library and a medical clinic. Jeffrey City even had its own local rag, the Jeffrey City News and in 1979, 4,500 people called Jeffrey City home. During this time First Baptist Church was established in Jeffrey City, a Southern Baptist church.

The Bust

Every boom must have its bust, and for Jeffrey City this came after the collapse of the uranium industry. What started with minor lay-offs ended with a cataclysmic shut down of the lifeblood and raison d’etre of the town – the mine closed its doors in 1982.

A population in shock, with very little prospects, were plunged deeper into crisis by the discovery of radiation in their homes. And so the mass exodus began. By 1985 a mere 3 years later, 95% of the population had left. According to the 2021 census, there are just 24 residents left in Jeffrey City and only 2 children are enrolled in the elementary school.

Today Jeffrey City for the most part is a ghost town, more akin to an abandoned Western film set than a thriving town. You’ll see more tumbleweed than you will people.

A Rich Seam Of Life

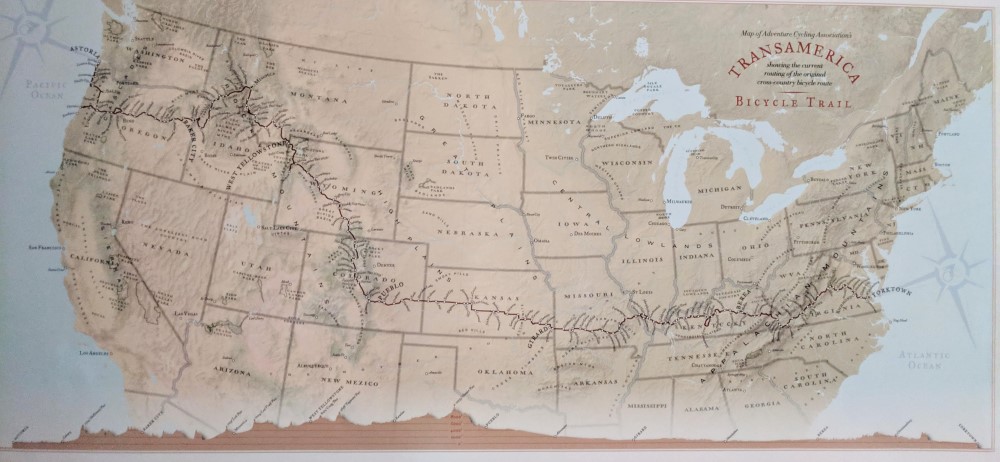

There is still a steady river of life that runs through the town – cyclists doing the TransAm, the trans America coast to coast cycling challenge. An online acquaintance of mine cycled through Jeffrey City and experienced the unique hospitality of the church that everyone thought had died. Some years ago the local residents noticed that many cyclists were coming though the town and they noted how hot and tired and sick of mosquitos they seemed. Many were trying to camp in ditches alongside the highway.

That led the church to open up its doors and allow cyclists to camp in the hall and to use the kitchen and bathroom facilities. To facilitate that, members of the Hilltop Community Church in Casper, Wyoming came together to repair the church and bring it back to habitable status. A number of church members either had friends there or hunted there (much of the remaining residents live on ranches surrounding the town) and that connection led to a campaign to re-establish the church. A mission trip was organised by a retired deacon to help complete the project.

Travellers Surprise

I began following Ian Finlay’s progress on Facebook through his page ‘My Endless Summer’ as he passed through my city on his way down the Eastern seaboard of Australia. Ian has a unique capacity to see life and culture through a refreshingly honest lens, picking up characteristics hidden from many others. After his Australian sojourn got rudely interrupted by Covid he eventually ended up post-Covid on the West coast of the USA with his trusty bike, determined to land in New York on the other side of the TransAm.

His route took him, like many TransAmer’s, through Jeffrey City. This is his description:

The city I was approaching didn’t have any stores of any kind. It gained its status back in the 1970’s when it was a prosperous mining community, mining for uranium. It then had all the amenities you’d expect in a city but when the political climate changed and when the digging became less lucrative, the city folk left. There are a few old-timers knocking around and I got to meet one of them. The new community is predominantly made up of people who were born within a few counties or those wanting to get away from society.

The locals rightly refer to it as a town, with only 50 inhabitants and I got to meet nine of them in the Split Rock Café/bar after establishing myself at the church nearby. Isabel served me a beer and made me cheeseburger and fries whilst I chatted with her husband of 32 years. He spent most of his time in his rocking chair at the end of the bar, brushing his cowboy hat and telling the guy to my right how well it has served him. It was profound how so much conversation could revolve around a hat but it reflected the pace at which this town raced. “How busy does it get in here?”, I asked. “This is it”, he replied.

It turns out that the tradition of people journeying through Jeffrey City is a long established one, that predated its boom town days. Now that the fuss of the boom has died down, the town has gone back to its roots of hosting through travellers. And so has the church.

After the collapse of the town the church closed down and eventually the roof collapsed. Through the help of churches from the next closests towns the church roof was prepared, monthly services were established, but most critically, it has become a kind of hostel for TransAm cyclists, shelter from the grind, and a place to rest and regather.

Although things get cold there in winter, Ian picked up on the warmth of the locals:

What struck me, is that everyone I later chatted to had a great sense of the city’s history in recent decades but also the significance of this area for the country’s western pioneers who passed through here in the mid 1800’s. It’s a difficult area to live in with the nearest food shop being 60 miles away. The winters are very harsh and I passed drift fences all along my ride. The town folk know each other well enough to pick up a few favourites for one another when they venture out for shopping. In winter the winds and snow will bury many of the single storey houses.

This is the first time I’ve heard people talk about hunting beyond the egotistical sport that is popular elsewhere. There’s elk, moose, deer, wolves and three mountain lions that roam here and its only when they venture out of the mountains and into the community that they may find themselves on a plate.

The church made a significant impression on Ian, and it’s fascinating to see the impact of the churches ministry of hospitality on him:

By now I’d established a mat to sleep on in a magnificent church on the outskirts of the town. I had considered staying in the town’s only motel but the owner was pretty rude to Norris the night before when he rang to enquire. I later discovered that the owner also fitted tyres occasionally and left motel operations to his partner who had just left him three months previous because he was always drunk. He offered Norris a room for $90 but couldn’t guarantee that it would be clean because he couldn’t get the frikin staff.

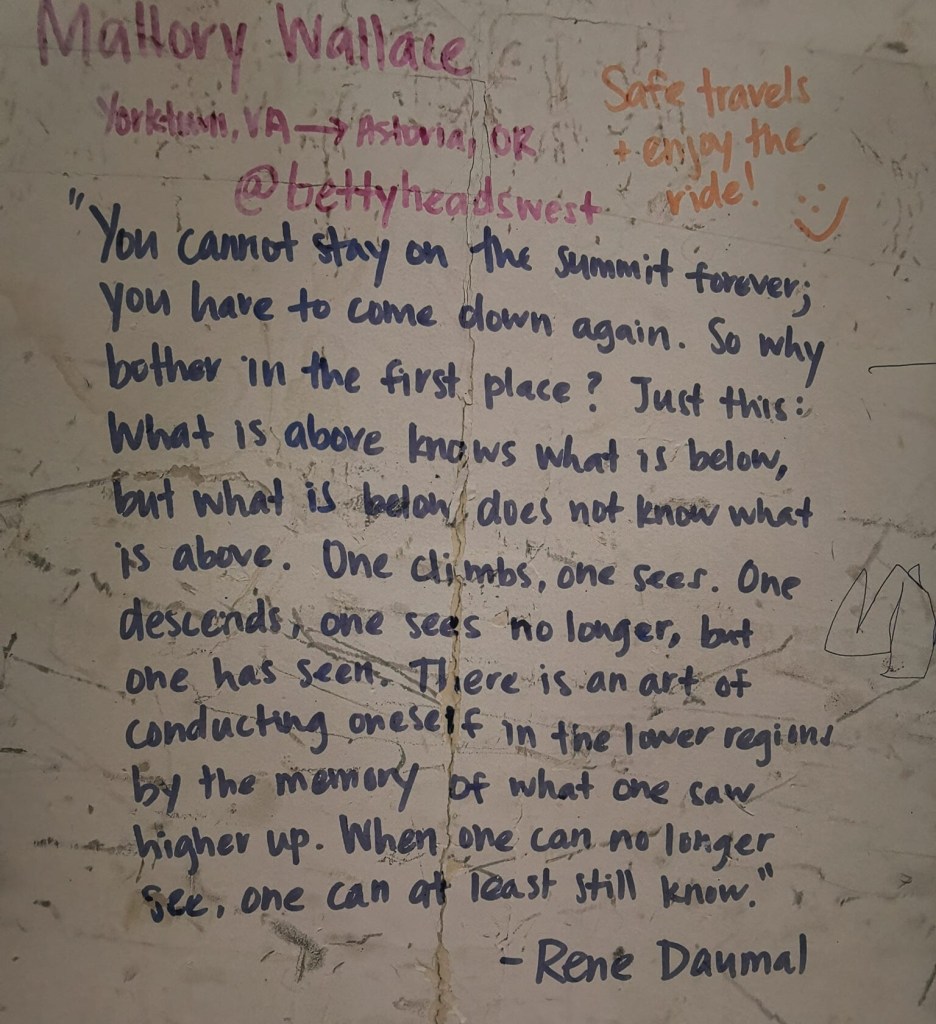

Before leaving the bar, I left a dollar bill with my name on it on a wall of thousands who had passed through. My Endless Summer waz ere; a small but memorable town called Jeffrey City, Wyoming. I walked back to the church building as the only resident but quickly lost an hour reading the comments and stories of all those cyclists that had been here before me. A young cyclist later arrived, showered and went to bed. He’d covered 90 miles in a headwind and the salt on his lycra confirmed his claim. He was heading in the opposite direction but his motivation was in the miles he clocked each day. He appreciated the church stay and was a pleasure to talk to but had learned little about the area he was racing through.

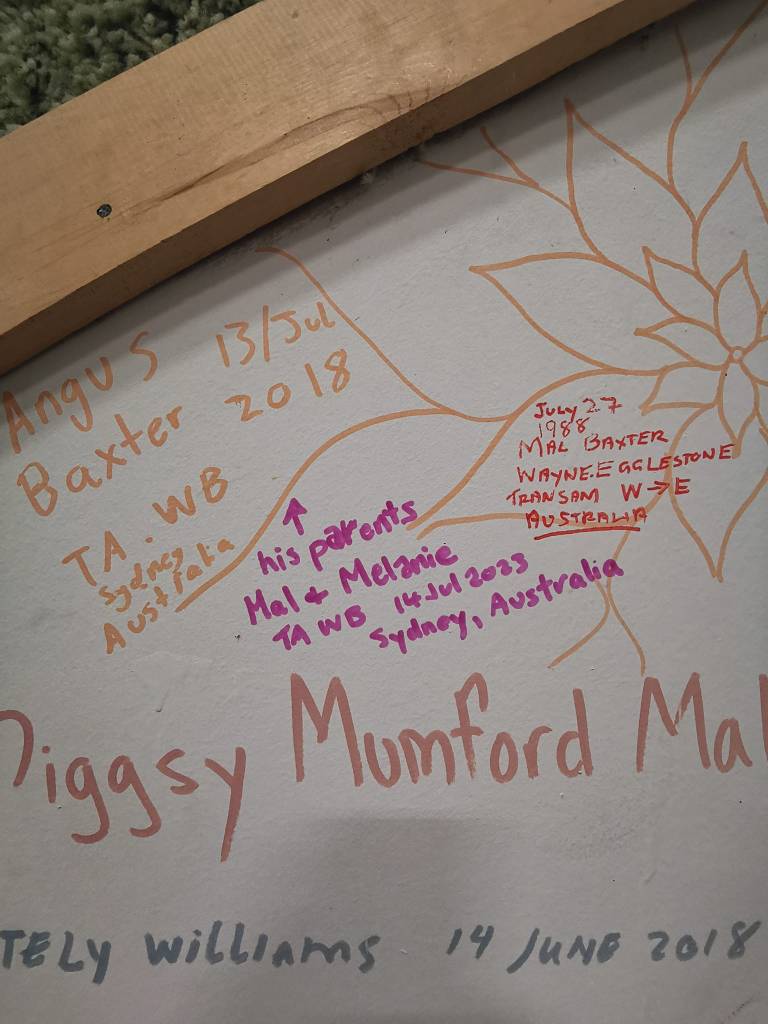

In the morning I met the gentleman who voluntarily managed the church hall to ensure that cyclists could make the leap across this wilderness. I was prepared to leave at 7:30 am but stayed and drank coffee, listening to his cycling related tales until 9. He told of a girl he saw crying in the corner of the kitchen in which we sat. When he approached and startled her, she pointed at a few words scribbled on the wall some 15 years earlier. “That’s my mum!, she’s gone now”, she said.

The church has such a rich cycling history, dating back to 1988 and getting here was an achievement in itself. One of the more isolated and least anticipated gems I have had the pleasure and privilege to experience.

Ian included a number of pictures to illustrate what he found written on the walls. Some are the usual inane scribblings you will always find on a wall, some are deeply profound motivational quotes:

“You cannot stay on the summit forever; you have to come down again. So why bother in the first place? Just this: What is above knows what is below, but what is below does not know what is above. One climbs, one sees. One descends, one sees no longer, but one has seen. There is an art of conducting oneself in the lower regions by the memory of what one saw higher up. When one can no longer see, one can at least still know.”

― Rene Daumal

Some are family connections such as the parents of a previous rider indicating their connection.

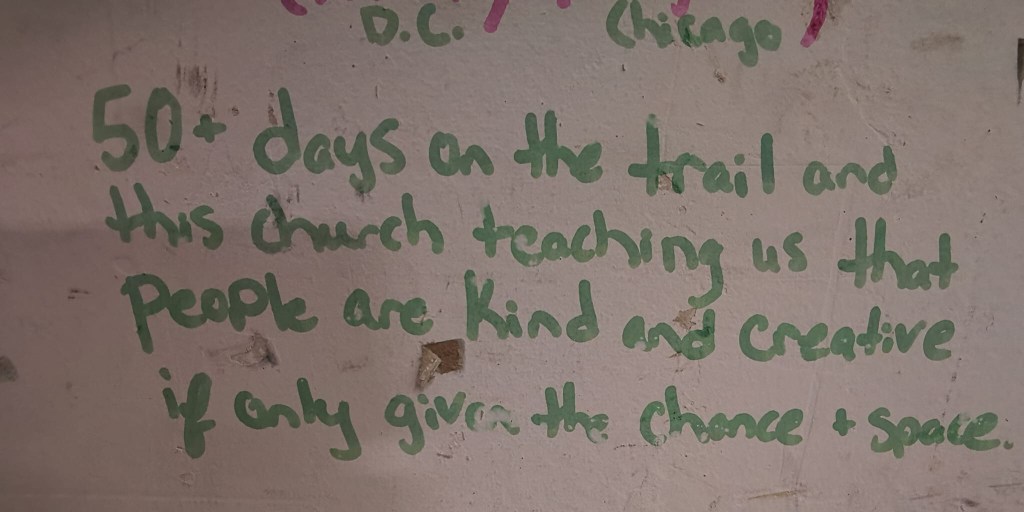

The one that impacted me the most was a comment about the church:

“50+ days on the trail and this church teaching us that people are kind and creative if only given the chance + space.”

Other churches would have given up and moved on many years ago. The Jeffrey City Community Church will probably never have a viable locally based congregation again or a pastor for that matter. It has a warden who lives in the local area who facilitates cyclists accessing the church.

Most of the people it ministers to will only ever spend a night at the church and keep moving on in the quest to cross America by bike. However, that constant stream of humanity is important, because every life is important. But in that one night or day that church through its warden can impact people for life and be a key stepping stone on the journey of faith towards faith in Christ.

The local mine has actually reopened with a 15 year plan to use modern technology to extract a further 15 million pounds of uranium but this won’t result in many jobs. Jeffrey City will remain a ghost town (the 2021 census revealed 24 residents left), with a beating heart located on the outskirts, where refuge, kindness and a listening ear can be found – motivated by the love of God and a missional principle that every life matters.