The paradox of trauma is that it has both the power to destroy and the power to transform and resurrect.

Peter A. Levine

Talking about or understanding ‘mental health’ isn’t a big thing amongst evangelicals & Pentecostals, and we Baptists in Australia find ourselves somewhere on that theological spectrum. The primary reason is the duality of our worldview, where some things are seen as secular and some as spiritual or sacred. Solving life’s problems comes down to praying because the answer is in the spiritual realm. Mental health disciplines are left to the ‘secular realm’.

Untold damage has been done historically through a misunderstanding of problems that people (especially children) have, where seemingly well-meaning Christians have sought to pray the devil out of people.

At one church I pastored, soon after arriving I noticed a guy who would turn up with a large mower on the back of a ute, and proceed to mow the lawn, only to leave when the job was done. When I inquired about him I found out that his wife attended church but that he never darkened its doors, but was prepared to mow the lawns. I went out to introduce myself and offer a cold drink. On the first week he declined but the next time he came in and so we established a relationship.

His child had significant mental health issues that had been treated as a ‘spiritual issue’ and at a previous church heinous damage had been done to him by some Christians who were convinced he had evil spirits in him. The resulting ‘ministry’ traumatised his child and he had subsequently and understandably lost faith in the established church and Christians.

Thankfully he started coming to church services and became more involved in the life of the church. As a couple, they made a point of encouraging my family and I and we experienced no end of kindness from them. They have moved up the coast where he is now the chair of the eldership in his new church. There were many lost years thanks to the inability of the church to understand aspects of well-being that lay outside of just spirituality, and the resulting damage caused to a child who needed care rather than being traumatised and gaslit.

A search of my own denominational website for anything related to mental health will produce some results for downloadable articles on stress and burnout, but that is pretty much it. Entry-level mental health. Despite Baptist churches being places of frequent trauma and conflict, you won’t find much on the wider aspects of mental health (beyond mere stress), or anything on trauma – despite so many people experiencing it through their lived experience in church. Mental health is an unexplored dimension that we simply have to start grappling with at a policy, ministry and care level.

However, this particular article series focuses on trauma – the darkness within that we dare not speak about. We need to become trauma-aware, develop trauma-informed ministry practises and also develop policies around how we seek to prevent it, minimise it, and respond when it does happen.

I choose to use the definition developed by SAMHA’s definition [1]:

A program, organisation, or system that is trauma-informed realises the widespread impact of trauma and understands potential paths for recovery; recognises the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff, and others involved with the system; and responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practises, and seeks to actively resist re-traumatisation.

A trauma-informed approach is distinct from trauma-specific services or trauma systems. A trauma-informed approach is inclusive of trauma-specific interventions, whether assessment, treatment or recovery supports, yet it also incorporates key trauma principles into the organizational culture.

A trauma-informed denomination and church reviews all aspects of its activities and identifies potential trauma events. It also recognises events that have happened that are most likely to have caused trauma and seeks to respond to the people concerned.

SAMHA’s way of putting it is [1]:

In a trauma-informed approach, all people at all levels of the organization or system have a basic realization about trauma and understand how trauma can affect families, groups, organizations, and communities as well as individuals.

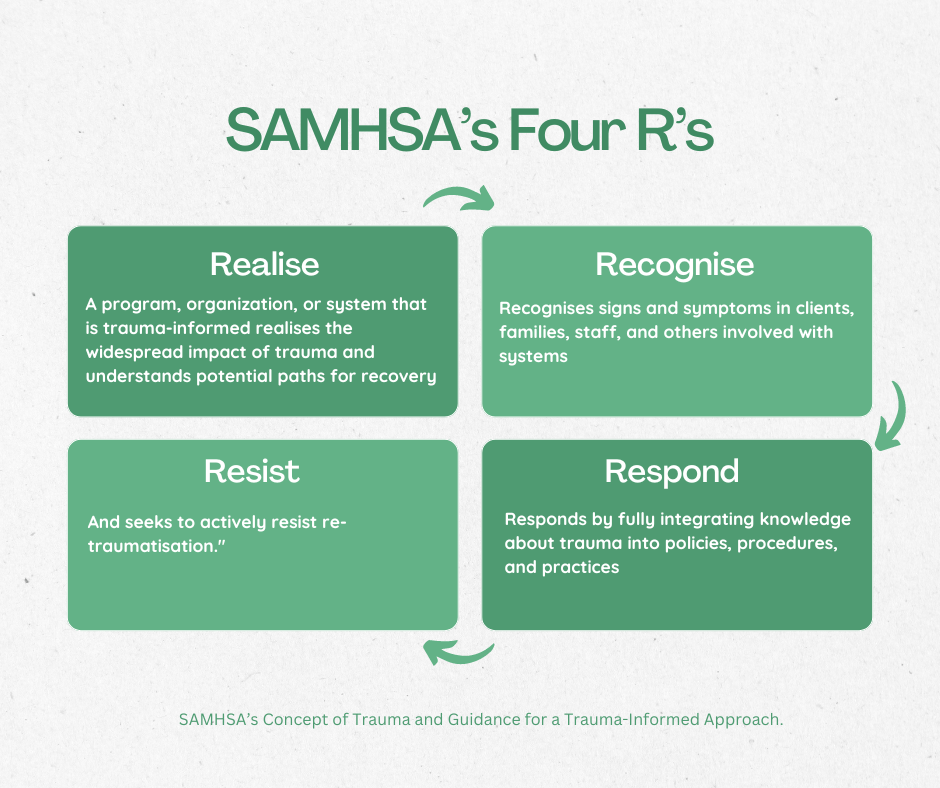

SAMHSA has placed extensive effort into better understanding and clarifying trauma-informed practice. Much of their work centers on “Four R’s:”

“A program, organization, or system that is trauma-informed realises the widespread impact of trauma and understands potential paths for recovery; recognises signs and symptoms in clients, families, staff, and others involved with systems; responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices; and seeks to actively resist re-traumatisation.”

What Does That Look Like For Baptists?

Firstly, we need to be brave and honest and realise that there is darkness within. Namely, that people are regularly traumatised in our churches, and that often, that trauma arises from how we choose to do church in our context as Baptists. It’s a hard admission to make because we feel like we are letting the side down.

We also need to recognise that our church communities reflect the broader community, and that means that we will have people in our congregation carrying trauma from non-church-related causes, such as abuse, violence, coercion and other significant events in their lives. How we do ministry should therefore be trauma-informed, and mental health-informed.

How do you think someone who suffers from anxiety feels when the pastor/speaker acts coercively and instructs the congregation to turn to the person next to them and say or do something? How do people like this feel when they are invited to walk down to the front of the congregation to receive prayer?

Having realised that trauma is a thing within our churches we need to review how we conduct not just ministry but other functions of church life that can often cause trauma such as church meetings, and pastoral reviews that are nothing more than kangaroo courts lacking in natural justice and pastoral sensitivity.

Secondly, we need to be able (through training, upskilling and awareness) to recognise signs and symptoms in our church family members who suffer in this way. Example: I recently heard of a church that initiated a pastoral search team to find its new senior pastor. After a round of interviews, they settled on a clear candidate. The eldership agreed with the search team and organised a church meeting to sign off on the candidate. At this point the candidate would have had a fair degree of confidence that the church meeting would approve of the nomination and that they would trust the work done by the search team and the oversight of the church eldership.

At the subsequent church meeting the candidate failed to attract the required percentage of votes, and the church membership went against the church eldership. By any measure, this is a dumpster fire of epic proportions. For starters, we have a bewildered, disappointed and wounded pastoral candidate. We also have a chastened pastoral search team whose many hours of work have been rejected, and we have a church membership that has rebelled against its elected leadership.

I found myself sitting next to an elder from the church at a meeting and asked how the church was doing. He seemed to think that everything was fine and that they would just “keep looking”. He didn’t understand why I thought it was a disaster. After pointing out all the ramifications of the disaster, and especially that there was a massive rift between the church membership and the leadership, he admitted that he hadn’t even thought through any of those implications. I encouraged him to consider that there was some serious work to be done before they embarked on another search.

This is a classic example of how churches fail to evaluate potentially traumatic events and to think through the ramifications.

Thirdly, having recognised these important factors, churches need to respond by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies (human resource management, church meetings, worship services, etc), procedures, and practices.

This may mean that you pull your pastor aside and ask them to quit with the casual coercion of “turn to the person next to you and…”,. It may mean that you choose to conduct church meetings differently, moving away from adversarial formats to ones that reflect your identity as a church family, and where bullies can’t prosper.

It may mean that you offer people alternative, sensitive forms of ministry after responding in a service that doesn’t turn their vulnerability into a stunt performed at the front of the church to demonstrate the visible results of the message.

It may mean that your pastoral reviews are conducted like they are in the real world: in a confidential manner by trained people using professional and fair processes that are fit for purpose and that reflect our values as God’s people – rather than the standard Baptist methodology which is anything but fair or ethical.

Fourth, we need to learn from our mistakes and resist re-traumatisation. It beggars belief that we have known for generations about how people get hurt in our way of doing church as Baptists, but we just keep doing the same thing. It is mind-blowing that the people who occupy positions of influence in our denominational structures don’t appear to be bothered by these facts. It’s mind-blowing that churches who experience trauma related to their systems don’t seek root and branch changes either. We as Baptists appear to have the lemming gene, forever falling off the cliff, only to climb back up hoping for the best.

Trauma-Informed Framework

SAMHSA’s “Four R’s” give rise to six key principles:

• Safety

• Trustworthiness and Transparency

• Peer Support

• Collaboration and Mutuality

• Empowerment, Voice, and Choice

• Historical, Cultural, and Gender Considerations

Pete Singer, Executive Director of Grace (Godly Response to Abuse in the Christian Environment) writes that [2]

There is a growing recognition of their applicability in the church. All of the principles are essential, and they overlap in their application. Churches should embed them into formal policies and procedures, so they are not dependent on a single person or group. As these principles are understood and implemented, personal and broader church culture and values naturally begin leading to trauma-informed practice.

Singer has written a brilliant article that helps churches and denominations unpack the SAMHSA’s work entitled ‘Toward a More Trauma-Informed Church: Equipping Faith Communities to Prevent and Respond to Abuse.’ I highly recommend this as required reading for everyone involved in leadership at the denominational and church level.

References & Links

[1] SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/sma14-4884.pdf

[2] Singer. Toward a More Trauma-Informed Church: Equipping Faith Communities pg 66

View of Toward a More Trauma-Informed Church (currentsjournal.org)

Leave a comment